Holmgren and Temford’s Ethics icon

(1) Care for the Earth

(2) Care for People

(3) Redistribute Surplus

These three ethics have always been at the heart of Permaculture thinking and teaching. At least, that is what folks in the Permaculture movement claim – including me. They are hard to disagree with too strenuously, no? This is partially because they so vague. This abstraction is part of their strength – they are widely appealing, and serve as a commonsense and positive entry point to draw people into a conversation.

The trick is, their abstraction is also part of their weakness. I have often found that the Ethics are taught in a watered-down and feel-good style, that does more to create good vibes and excitement than it does to challenge students, or help designers navigate the sometimes-murky waters of choosing clients, partners, and projects. If they get reduced to a story abouttending our garden, then sharing our kale with our friends, and thencomposting our “surplus” kitchen scraps back into the garden, then what does the movement really gain by having ethics at all? Other than to say – in Permaculture, it is so easy to be ethical!

The way I think about the Ethics – and the way I train future designers – revolves around the idea of putting some teeth in Ethics. “Care” is a tricky term, after all – it can refer to emotion alone. Like: “In my heart, I truly care for the Earth, and so I shed a single tear every time I turn the key and start up my Hummer.” I prefer to think that, as used in the Ethics, it refers to the action of caring – of taking care of something. So the question becomes, how do we know when we are taking care of the earth, of people?

This is a question that each of us should spend time on, and revisit. We can and should choose indicators and benchmarks, to help us know when we are following the Ethics we espouse – and when we are coming up short. Specific measures are up to the designer, but there are a few questions that I think the Ethics demand that we ask, and ask repeatedly.

Care for the Earth: What, really, is our measure of ecosystem health? The most popular in the Pc movement seem to be biodiversity and energy capture, but I would easily accept topsoil depth, presence of top predators, decreasing levels of nutrient or contaminant runoff in surface waters, structural/functional diversity, etc. What matters to me is not which indicator is used, but that there IS one. We need ways to measure our results – and to see if we measuring up.

Care for People: What is our measure for social health? A trickier question, even, than measuring ecosystem health, but we still have to spend time thinking about it if we want to accomplish it. The questions that emerge from this Ethic are:

How is this project helping this community USE AND CONTROL it’s own resources regeneratively? How is this project helping a community take control of its own destiny – to self-determine?

It may not be as easy to come up with a number or a measure for this, but I want to hear you (and me) at least make an honest and compelling case for how our work is doing this.

Redistribute Surplus: Trickier still, this third ethic, and most often neglected. And exactly as crucial as the other two. This one merits a little digression.

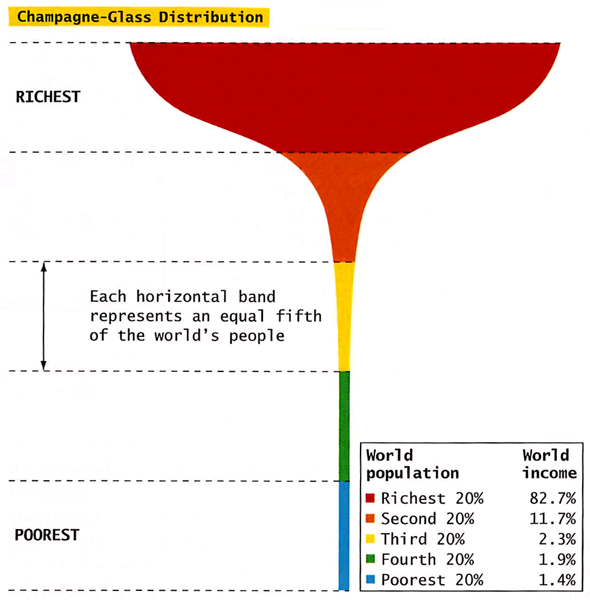

Most introductory Permaculture presentations start with an “Evidence” section – a presentation of the most compelling evidence for the need to do something different – and not go on as we have been. That’s classic Pc, as many folks are aware – to spend just a few minutes on doom and gloom, and then focus on solutions for the rest. I present the usual littany of bummers for my evidence section – deforestation, soil loss, climate, peak, etc. etc., and then as the last item, I put up a slide on “Inequality.” I use this graphic for the slide:

Source:contexts.org/graphicsociology/files/2009/05/conley_champagne_distribution.png

I leave this slide up, while we have a little discussion on “Why is inequality an ecological problem?” The discussion that follows is generally very productive.

These are my own answers:

(1) Because of the environmental EFFECTS of inequality: poor communities are unable to defend themselves against toxic contamination, and have no buffer against instability in the economic and ecological systems, so bear disproportionate effects – especially disproportionate when compared to comparatively tiny ecological footprint of these same communities.

(2) Because inequality is an environmental DRIVER: as long as their are people making decisions about production and extraction who are making a killing from it, and who can also shield themselves indefinitely from its effects, while at the same time those who do the work and actually bear the brunt of industrial fallout don’t have any decision making power about production and extraction, there will be no sustainability. Research supports this statistically: in counties, states, and nations (3 different studies) the more inequality, the worse the environmental outcomes. When the benefits go to power-holding decision-makers, and the detriments go anywhere else, why would we even expect the system to change?

(3) And finally, because it’s just freaking ecological, isn’t it? The movement of energy and matter through complex living systems is the stuff of ecology, and we can use that lens, and those tools, to understand it and to change it.

SO, back to the 3rd Ethic. The way I see it, the question that the 3rd Ethic “Redistribute Surplus” demands of us is this:

How is my work helping, in some way, to begin to flatten the terrible mountain of inequality that lies between us and true sustainability?

Or, to reverse the metaphor…

How is my work helping to fill the chasm that separates the 80% world from the 20% world, that MUST be filled to regenerate our culture and our biosphere?

These are the questions that I try (and sometimes fail) to put at the root of my Permaculture practice: design, research, and education. I’m confident that there are jobs that I don’t get because of this. These are the questions that I try and inculcate in the slowly growing horde of amazing, inspiring change-agents, that I am privileged and amazed to call students. These are the questions I would like us to be asking each other all the time, and asking of the projects and partners we consider supporting – especially but not only the ones we call Permaculture.

In this light, the Liberation Ecology curriculum is all about an in-depth, design-driven exploration of the Ethics. What does it take, after all, to create a project that can answer this set of questions substantively, and in the affirmative? It takes more than the Principle of Multifunctionality and the Scale of Permanence, I figure. I’m pretty sure of this, actually. If we want to build a movement that works – that gets us the world we want to live in – then I think it’s (past) time to put some more of that critical design thinking that we pride ourselves on into the design of the movement itself. Leavening the feel-good and inclusive nature of the Ethics – with some provocative questions – is one way to do it.

Comments

2 responses to “Putting Some Teeth in the Permaculture Ethics”

Thanks Rafter for talking at length about equality in your ethics.

Thanks and your welcome, Louise. I’m pretty sure I’m just articulating what a lot of us feel.