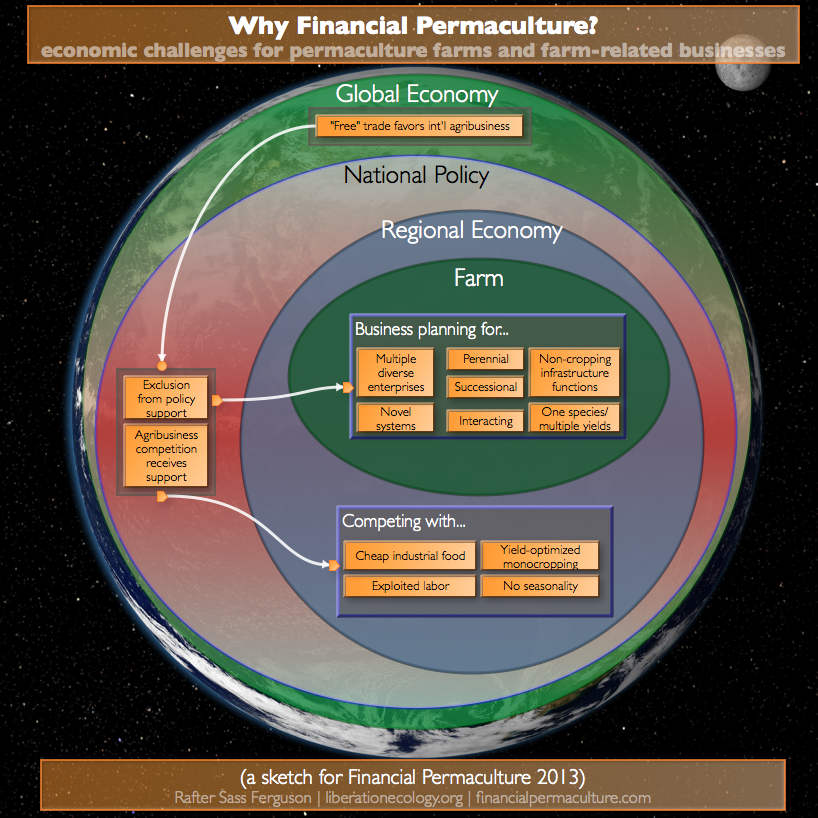

Permaculturists face a wicked contradiction. We want to create, and support the creation of, businesses and organizations that point the way toward a new way of doing things. If we want to claim that permaculture is ‘design that meets human needs while increasing ecosystem health,’ then we need to be able to demonstrate how the enterprises we design are meeting this description. Otherwise, our ethics aren’t meaningful, and the claims we make about the value of permaculture aren’t credible.

The trick is that these enterprises also have to thrive right now, under industrial capitalism. If no one but the independently wealthy can use permaculture systems to both survive the current society and transition to whatever comes next, then permaculture isn’t much help at all. I don’t want to make lifeboats and pleasure gardens for the rich, and I don’t want to have to wait until after the apocolypse for permaculture to make good economic sense.

So there is our contradiction: we have to make truly regenerative enterprises that can succeed right now, enmeshed in a grossly degenerative socio-economic system. We have to make a future that can survive the present. I’m grateful that the Financial Permaculture series is helping address this challenge directly and with great intelligence – which is why I’m teaching at the upcoming course for expenses only.

The permaculture literature mostly deals with the tools and the opportunities available – so I’m going to keep focussing on the challenges. With this post I hope to frame some questions, and generate discussion, about the challenges we face – particularly the two major challenges that I see for permaculture farms (and for the many who work and farm permaculture-style without having been influenced by permaculture proper).

- At the scale of the farm itself, very few planning tools exist to support the level of diversification that permaculture farms will usually show. Even fewer tools exist to support successional budgeting and planning for perennial systems – the yields of which will change over time. Permaculturists who integrate animal, perennial, and annual production face a significant challenge in figuring out how to integrate the tools that are available – or create their own – so that they can do the necessary planning to ensure the viability of their business.

- Beyond the farm boundaries, permaculturists find themselves in competition with cheap industrial food, whose price is subsisidized by cheap oil (and the wars that secure it), pollution, exploited labor, and tax dollars (via government subsidies). We have the local and slow food movements to thank for a growing base of educated consumers who will pay a ‘premium’ (ha!) for food whose price isn’t kept artificially low by degenerative practices – but these niche markets don’t exist everywhere, and they won’t get us all the way to where we need to go.

So how do we adapt and combine existing farm business planning tools for permaculture systems? How do we adapt and combine progressive business models that will permit regenerative enterprisees to thrive in the current system? What have you seen work, or fail?

Comments

14 responses to “Toward Financial Permaculture: New Farms in the Old System”

Technically, there are so many options, but the basic question is: how to make enough money to continue operation? One option is the Polydome.

Permaculture within greenhouses is quite new; Eva Gladek worked for us (InnovationNetwork/ Dutch thinktank ministry of Agriculture) on the design of such a system. She recently made detailed designs for three cropping combinations; the general report can be found on our website: the concept is called Polydome.

We now have several ‘regular’ greenhouse growers interested in the system. With a large number of different crops, a grower can operate downstream the value chain. However, managing demand and supply is not easy. Typically, box systems do quite well as growers can then decide what to sell.

Hi Peter – thanks for your comment! I’ve really enjoyed your work with appropriate technology for mushroom production – it’s great to have your input here. (That was you, right?). It looks like you have you moved on to more great work… which everybody can check out here: except.nl/en/#.en.projects.1-polydome.

I think the question is really “how to make money while still regenerating social and ecological health” – i.e. not selling out. And I’m generally quite skeptical of the hi-tech and capital-intensive “vertical farming” models that get thrown about – generally by people with no real background in sustainability or systems thinking – as the way forward for cities. At the same time, the urban environment obviously demands a much higher ratio of innovation:recovery than rural systems. It looks like the Polydome project might lie in that sweet spot. I’m looking forward to implementation reports!

I think a look at the historical use of currency can help us imagine the next level for the exchange of goods & services & value.

From my blog Cultural Succession: Journaling the meme that Healthy Human Cultures Naturally Regenerate through Distinct Phases similar to how a Forest Regrows after a major Disturbance (labeled ‘X’). Native Cultures -X-> Agricultural Civilization –> Industrial Civilization –> Cultural Creative –> Digital Native

Currency Through The Cultural Phases:

Indigenous -> Gift Economy via Barter, direct-trade

Agricultural -> Barter, direct-trade, currency of gold & silver

Industrial -> Paper money, fiat currency, debt currency, divested from gold standard

Cultural Creative -> Local currencies, Alternative currencies, Time-banking, College Credit, Internships

Digital Native -> Glocal currencies, Complementary Currencies,

Open-Source Currencies, Digital currencies, Promotional Currencies, Game-Based Rewards

For a more in-depth look at the Cultural Creative currencies and the up-and-coming DIgital Native currencies that we can implement to reward volunteers, students, and each other for co-creating a regenerative world, please see: http://culturalsuccession.tumblr.com/post/32812051831/currency-through-the-cultural-phases

Thank you for this post Rafter, and thank you for being involved in financial permaculture [I’ve participated in FPC in the past]!

On “financial sustainability:” Although I believe that there are a multitude of solutions for permaculture to become commonplace, I don’t feel as though trying to make permaculture competitive in the extractive economy is a particularly viable long-term strategy [except in a minority of niches, as it’s done so far]. You mention that you’d prefer not to accept help from the “independently” [more accurately, dependently] wealthy. Might it be, that for a regenerative economy to be born, the extractive economy and it’s financial resources need to be devoured? I find Charles Eisenstein’s perspectives on gift insightful on this subject. Conversely, if the extractive economy derives profit from exploitation, wouldn’t a regenerative enterprise become a paradox in this environment unless it let go of the attachment to financial profit?

Just musings – I know there are those in our community with the opposite view.

The best answer to your questions that I have seen is Restoration Agriculture: http://restorationag.org/

Based in WI, Mark Shepard is essentially doing farm scale permaculture. He also recently published a book on Restoration Agriculture, named after it. This is what we aim to do with our future farm.

I would second that. Do you know if Rafter is going to visit New Forest Farm???

Hi Tom & Beth. I will be visiting New Forest Farm during my research.

Mark’s book was definitely interesting, and I’m excited to visit his farm.

What specifically makes you say that it is an answer to the questions I’m posing above?

Hi Rafter, I’ve heard it said in business (which I know very little about…I’m a high school health teacher) a saying that you need to be able to change with the markets or something like that. You need to adapt. My friend’s dad growing up ran a photo shop business and a portion of the business was printing film. Not too many people doing that anymore. They had to adapt to this. Dave Chappelle had a skit on his show (which I don’t recommend) that had a couple of Wu-Tang Clan’s members posing as mutual fund brokers and they said something like “diversify motha f#ckas” and it was this kinda funny/inappropriate look at how some people see not putting all your eggs in one basket.

I think permaculture is big on both of those. Adaptability, diversity. Like you said, the slow food and organic movement has done much to help transform our food system. When a conventional grower switches to organic, we praise them. It’s still not perfect, and I think a farm like New Forest might be something I’ve heard of as that next step: from organic to permaculture.

Thanks, Tom. That makes sense to me.

[…] If you would like to comment on this article here you are welcome to. You may also want to continue the great conversation that is on Rafter’s blog. […]

I agree that a lot of new, sustainable technologies or products/services tend to only be accessible to the wealthy (ie organic food, permaculture design systems, sustainable building design, etc.), which goes against the values of the goal of moving towards wide adoption of sustainability and access among all income levels.

HOWEVER, we can see this as only a PHASE, where the wealthy are simply the point of entry. The door needs to be opened by whoever has the resources initially, in order to forge the new pathways towards more widespread access. Of course, if it STAYS that way, this is a problem, but this is unlikely to happen if permaculturists and activists continue to hold the bar high, and as more people are able to see the examples of what is possible.

Hey Amanda. Thanks for your comment – I’m with you that people with more resources have a lot to offer in terms of helping to establish the infrastructure that will support more inclusive participation.

Would you explain your metaphor a bit? What is the door? What is actually happening when wealthy people are opening it? What’s the bar?

Thank you for helping to hold me to a more precise standard with my rather vague suggestions. By opening the door I meant ‘breaking new ground’ as pioneers–pushing past the initial blocks to momentum in initiating something new. You could look at it as creating new pathways, both neural, relational, cultural, and economic.

For example, culturally or individually, sometimes people need to see actual real-life examples of something novel (ie growing food on a skyscraper rooftop) in order to activate a vision, feel inspired, and to believe that it is actually possible rather than a nice but unrealistic fantasy (creating new neural associations and neural pathways).

Sometimes more ethically-created products as you know might involve more expense and sacrifice on the part of the producer/seller, which will need to charge a higher price in order to be economically viable. If ethically-minded wealthy people are initially the ones who can afford these higher-priced products, it could create visibility, an increase in demand, relationships among suppliers/producers, social and economic infrastructure to support it’s momentum. This could also create the means to experiment/innovate to make the products more efficiently/cheaply, and potentially even bring the production up to a higher scale which would reinforce the virtuous cycle of becoming more widely accessible to diverse income brackets.

By ‘ raising the bar’ I mean to continue to monitor the cultural changes that are on a culturally progressive edge and find ways to make them more accessible. So for example, if alternative products/services/technologies are initially out of reach to the average person, at some point enough social innovators involved with this cutting edge will understand that they are only truly sustainable if they are accessible on a broader scale.

A simple example of this would be more recent movements (such as the People’s Grocery) to provide healthier, organic food options to lower income people in Oakland, as well as partnering with these communities to grow organic food locally. These small-scale (but growing) projects on their own aren’t going to change the economic structures which allow conventional food to be artificially cheap, but as part of a larger landscape, these activists are tapping into the growing interest in finding innovative ways to push organic food beyond the confines of high-end farmers’ markets and boutique grocery stores.

I hope this makes sense, and I appreciate the conversation.

[…] I’ve written before about the challenges faced by permaculture enterprises. Farms, like other land-based permaculture projects, are faced with the formidable task of regenerating ecosystems and communities, while surviving in a system that rewards the destruction of the same systems. Permaculture projects have to compete with degenerative enterprises and institutions that are happy to take the efficiency ‘bonus’ from unsustainable and exploitative practices. […]