Now that Toby’s interesting essay (in response to my post on definitions in permaculture is making the rounds, I think it warrants a reply. (Some of this post assumes some prior knowledge of those posts, and a general awareness of agroecology).

If you haven’t read Toby’s piece, he’s making an argument that permaculture is really, fundamentally, a design discipline – and that’s how we should regard it. It’s not a movement, a set of practices, or a worldview, and we shouldn’t confuse it with those things. It’s clear how this reduction could be attractive for people who are interested in supporting the professional sector in permaculture, and Toby makes his argument well. His definition tidies up a messy ecosystem, drawing clear boundaries that focus attention on a single aspect of interest. While such linear and reductive thinking can be useful in the right context, in this case it does not serve.

Permaculture’s spread has been fundamentally shaped by its social movement aspect. In particular, two distinctive and explicit strategies for growing the movement were articulated and demonstrated by Bill Mollison – itinerant teachers and bioregional organizations. Mollison strategically, brilliantly , (and problematically), traveled the world on a shoestring for decades to grow the movement and plant the seeds of bioregional organizing – and in doing so set the stage for thousands of others to do likewise. These distinctive strategies for movement growth continue to fundamentally shape how people encounter and participate in permaculture. Permaculture, as a whole system, has nothing to gain and much to loose by disavowing this aspect of ourselves.

Parallel arguments can be made about the distinctive characteristics of permaculture as worldview and practice, but that for a later date. (I make some of these arguments more comprehensively in a paper that is now in peer review – still deciding if I will release a preprint or wait until I’ve done the inevitable revisions.)

Toby makes an illuminating comparison of the spread of permaculture with the emergence of scientific thinking during the Enlightenment. He notes that, while the emergence of (for example) chemistry may have appeared inextricable from a movement and worldview, we can now see clearly that it is actually just a humble, apolitical, purely scientific discipline. This is a dangerous romanticization of scientific history, and of how science actually functions in the real world. If chemistry appears as a pure discipline now, it is because chemistry-as-movement was successful in promulgating it. Think of climate science. Think of GMOs.

We could probably agree that agroecology, today, offers a better comparison with permaculture than chemistry from two centuries past. Wezel et al. offered a well-cited definition of agroecology as simultaneously a scientific discipline, a movement, and a practice. For those of you who don’t know, agroecology is well established as a scientific discipline in much of the world (less so in the US), despite only really coming into being in the 1970s. Agroecology as a movement is most powerful in Latin America, in particular, where shows itself in part as Campesino-a-Campesino (Farmer-to-Farmer), an international network of peer-to-peer education that permaculturists could learn a lot from (and are).

What would it look like if Wezel et al. had instead written this: That movement? That’s not really agroecology. Only the scientific discipline is really agroecology. We only think the movement is also agroecology because we’re confused about paradigms, and one day we’ll look back on this and it will all be perfectly clear. To be clear, Wezel et al. would have much more evidence to support that assertion about agroecology than we have to support the assertion that permaculture is simply a design discipline.

In that counterfactual scenario, if the authors hadn’t been laughed out of town, they would have done a grave disservice to agroecology. The strengths and successes of agroecology are entirely dependent on the whole complex ecosystem: the rich and dynamic relationships between researchers, networks and organizations, and campesinos testing and developing practices on the ground. Agroecologists would have have been cutting themselves off at the roots.

In fact, some agroecologists (including my former advisor Ernesto Mendez) responded to Wezel et al.’s piece by asserting that drawing distinct boundaries between the different sectors of agroecology would be antithetical to its most distinctive and powerful qualities: transdisciplinary, participatory, and action-oriented. (Remind you of anyone?)

As Mendez et al. rightly observe:

The connection between agroecological practice, equitable distribution of resources, and self-determination has been made explicit by marginalized communities demanding justice through food sovereignty.

This is no less true for the terrain that we face as permaculturists. And while permaculture isn’t agroecology, and we needn’t try and be agroecology, we are clearly fellow travelers. We should take note that it is precisely agroecology’s evolution as a complex multisectoral system that produces…

…agroecologists are aptly positioned to contribute to these struggles by participating in a creative process of knowledge production with farmers. This requires a broader understanding of knowledge and learning as a community of practice that involves both farmer scientists and university-trained scientists. Agroecology, through its parallel development as a science and social movement, is an apt site to construct relevant agroecologies that address asymmetrical power relations.

If you replace ‘farmer’ with the broader ‘land user,’ and ‘university-trained scientist’ with ‘experienced designer,’ how apt a description is this of what we are striving for in permaculture?

In short, we should go ahead and embrace the whole ecosystem of permaculture, and not settle for convenient definitions. I’m all for shorthand definitions in the right context (which is why I still say meeting human needs while increasing ecosystem health), as long as it’s being used to communicate a principle rather than obscure fundamental complexity. While the professional sector in permaculture might stand to gain in the short term by disavowing our history and our complexity, permaculture as a whole does not. No roots, no harvest.

Edited 6.15.13 to include more links and expand discussion of agroecology.

Comments

31 responses to “the convenience and poverty of simple definitions”

It seems like you and Toby are both trying to help validate permaculture’s importance. He seems to believe that the best way to do this is to simplify how it is seen and defined. He believes if it is seen as a design practice that this will help it be implemented and respected on into the future. It seems that you believe that the complexity of all that has gotten permaculture to be what it is today needs to be preserved in order it to have the power and longevity it needs. You are both reaching out to science in your work and seem to have taken positions based on what you think will give it a lasting place in our relationship with our ecological environment.

Thanks Rafter, for putting words to my disquiet with Toby’s reductionist approach to defining permaculture.

You’re welcome, Dave. Toby’s piece is so interesting and erudite that it took me a while to realize how ardently I disagreed with it.

I’m really appreciating this back and forth dialogue, it’s a very worthwhile conversation to have.

I would tend to simultaneously agree and disagree with both of you. That is, you’re both right. Rafter, you’re correct in that given the definition of a movement, which is “a series of organized activities working toward an objective”, in that sense, certainly that is what permaculture is. We are working as individuals and a collective, just like the civil rights movement, to bring a different world into being. However, to bring Toby’s sentiment to bear, the movement is based around this method of design. It’s not a movement based on nothing, but rather a movement based on a specific set of ideas and practices. Also, it’s most definitely not a philosophy. Sure, one could ponder the philosophical implications of permaculture, as a practice and a movement, but that is not permaculture in and of itself. Permaculture is compatible with a wide varieties of philosophies, religions, and spiritualities. We’re not questioning the fundamental nature of reality here, we’re simply looking a different way of interacting with the world. It’s only a very superficial, non-sectarian way that you could call permaculture a philosophy.

Where I would tend to agree with Toby most is in the idea that we need to really start defining ourselves in a way that people can clearly and easily understand. That’s not to say that we should diminish it’s place as a movement, but like the definition given of agroecology, we should say confidently and proudly, that it is a scientific discipline, a movement, and a practice. No more pussyfooting around the issue. Unfortunately, this is the tradition that has been passed down, that’s it’s a vague definition, and that everyone defines it differently.

As an illustration of how problematic it can be to have a vague definition, let’s look at your definition of permaculture as “meeting human needs while increasing ecosystem health”. This is a really great definition, but I think that it is flawed. The reason I think it’s flawed is because there are ways of increasing ecosystem health that are not permaculture. For example, take the native americans. They lived abundantly off the land for thousands of years, while increasing the health of the ecosystem. There is even a modern tribe managing an extremely large tract of forest, where the number of board feet has only increased over the years. Yet, they are not using permaculture design in any way. Is that to say that permaculture could not have achieved the same results in the long run? It’s certainly possible that it could have. However, permaculture does not have a monopoly on environmentally beneficial practices. It is but one of many approaches that can help guide our individual and collective actions in a more ecological direction. For more on this, look at Darren Dougherty’s Regen10, in which he includes permaculture among ten other techniques that land managers, designers, and planners can use to create regenerative systems.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MvVlzUv8D5U&feature=share&list=PLqPZgDXOa8vdul6QcsTQS_PXgzPEcu5-4

So I do think it is very important to narrow our definition of permaculture, while being realistic and sensible about it’s general characteristics. “What permaculture isn’t” is actually quite beneficial to permaculture, as it allows us to more firmly define exactly what we are talking about, and thus more clearly explain what we are doing.

It is what it is.Who cares what definition you chose to work with,

really.

Permaculture is not a movement! I’ve always taken exception to people who say it is. I think there’s been a diluting of the word ‘movement’ to only meaning something popular, just like there’s been a diluting of the word ‘revolution’ to only mean something new, as in “the meat slicer revolution” or “a revolution in personal body care”. Movements are more than popular takes on things. They happen when people get organized. Permaculturists are not organized as a group. When you apply the design process to philosophy, social permaculture, or financial permaculture you have a hundred different takes on things, and we’re certainly not applying any one of those takes on a way to organize permaculturists together. There are people that apply the Fairshare ethic to the idea of egalitarianism. There are others that apply it to sharing the leftovers. There are some that skip the ethic altogether. I have even heard some people apply a concept of financial permaculture to the book Rich Dad, Poor Dad, a book the promotes passive income by exploiting others. There are some that apply social permaculture to Consensus decision making, and others that are very individualistic. So, there are lots of philosophies that we like to discuss and promote, but as a group, permaculturists are not organized.

Permaculture is not a movement, but it would help us to apply it to our work in various movements.

Thanks for the thoughtful writing Rafter and Toby.

For some reason I can’t escape from the feedback loop connecting my practices and movements with my design process and vice versa, all of which are nested in my worldview;) Of course that’s my subjective experience. Perhaps we can find appropriate niches and scheduling for all to fit in and synergize.

Actually, yes it is:

http://www.files.chem.vt.edu/chem-ed/ethics/

Furthermore, there is no reason that including ethics would exclude something from science. I believe that science without ethics is simply faulty. The only way to do science in a way that does not violate the natural and cultural structures in which we operate is to use ethics as a guide to your overall approach. So while I agree that permaculture is most definitely more than just a design science, it is none the less definitely a science.

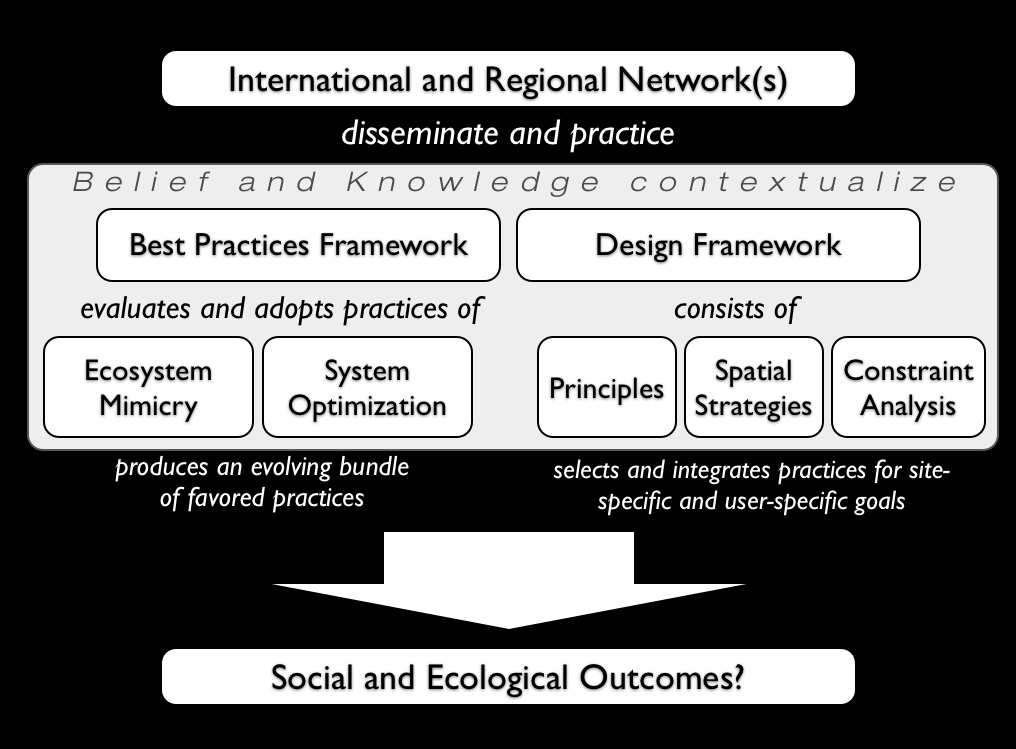

I practice permaculture as a design discipline. I don’t see much of a unified permaculture movement other than the hundreds of thousands of people who are using permaculture design in their work. In that case the movement would be made up of people who practice permaculture, and therefore permaculture would be the design discipline that people practice. It is tempting to let permaculture be defined broadly, to be somehow all-inclusive, but it is what it is (straight out of Mollison’s PDM “design is the subject of permaculture”; for what it’s worth;). Personally, I don’t know how to practice permaculture as a movement, other than teaching and creating more practitioners who go out and redesign their lives, their neighborhoods/villages/communities, the world, i.e. creating practitioners of the permaculture design discipline. Pragmatically, that is what matters to me as a designer and teacher of permaculture. If a movement is desired to do that, then call it the “movement of permaculture practitioners”, but don’t confuse the movement with permaculture. What I care about most with the term is that people are actually using “Permaculture Design” rather than some set of agroecological or natural building techniques, or whatever. Permaculture is the design framework that all of these techniques need to be hung on, so that we can wholistically develop solutions to problems to avoid having our solutions create new problems (which is often the case with fragmented design, and one aspect that gives permaculture uniqueness). In the end the term “permaculture” doesn’t matter. It’s about the work we do with it. So we would be wise to ask ourselves, what is the purpose of the term? To me the purpose of the term permaculture is to make clear what separates it from other seemingly similar things. I can understand the desire to participate in a movement, but movements are based on something. In permaculture that something should be wholistic ecological design. Is that reductionistic? Maybe.

Permaculture is most certainly a social movement because of its structure of education and loosely connected organizations. As Permaculturists, we must not forget our history. As many of you know, Permaculture was born as “a positive way forward” in a direct response to the negativity propagated during activist-based regulatory environmental social movements of the 1970’s. As a social movement, Permaculture closely follows the legacies of the environmental movement, which can be seen as loose, non-institutionalized networks of informal interactions that includes individuals, groups, formal and informal organizations that are engaged in collective action motivated by a shared identity or concern about environmental and related social issues.

This is a really important point, Gretchen. We can’t reduce permaculture to a mere design science when its core ethics are huge: care for the earth (a big job!), care for the people (equally daunting) and fair shares (you can’t say that’s not political!).

My understanding is that permaculture isn’t based solely on modern Western science but also includes insights, ethics and practices from traditional indigenous culture, presumably of Australia. If so, I believe that’s the true genius of it – and part of what separates it from the field of agroecology. I doubt that modern Western science alone is capable of rescuing us from this mess of its own making. I think we have a much better chance of a decent future by including the wisdom of traditional, more nature-harmonious cultures with the best of modern science. It’s important to remember that modern Western science is itself not free of limitations and bias. It has a cultural history and point of view (dare I say philosophy?) and isn’t just “truth.”

On the contrary, agroecology was founded explicitly on the basis of understanding and valuing (and fighting to protect) indigenous and peasant agriculture. It’s a far different approach to doing science than conventional agronomy.

Rafter, thanks for the excellent critique. You’ve done me the honor of making an honest effort to represent my views accurately rather than setting up flimsy straw men to bash down. There’s a lot to chew on, It triggers for me about four avenues of thought, so for now I’ll restrict myself (mostly) to one, the idea of permaculture as a movement. We’re in broad agreement in many areas, but that one is the place where I think we diverge the most. The other avenues we’re much closer on. This is, as is usual for me, a pretty long reply.

First, my article was more about what permaculture isn’t than what it is. In that sense, the article was indeed reductionist: I am trying to winnow away some of the unneeded and unhelpful baggage that permaculture has accreted over 30 years, and see what its truly essential properties are. I am looking for a way to think about permaculture that is the most useful in terms of applying it toward creating solutions, explaining it to people, and to teaching it. I am looking for the pattern behind permaculture that enhances its development.

I have never argued that it is a design science. It’s not a science, because we rely on pragmatic “does it work or not?” methods far more than on a scientific search for falsification or mechanism. And I don’t think of it as a discipline. Disciplines have boundaries, and permaculture is highly inter-disciplinary. I find it most useful—meaning most productive of insight, guidance toward valuable work, and having broadest application—to think of it as a design approach, which, because it links and transcends disciplinary boundaries, can be used to solve virtually any challenge we’re facing. “Approach” is not a great word, but it’s the best I have been able to come up with. Permaculture is a pattern of strategy development for arriving at sustainable solutions to almost any problem.

I agree that we need to honor its social development. Mollison’s strategy of decentralization, grass-roots development, and itinerant teachers was brilliant. But many ideas have spread in the same manner—much of early science, schools of art and philosophy, techniques, national myths, even civic organizations. Just because something develops via a social network doesn’t make it a social movement. In this sense, permaculture is more like a meme than a movement.

Mollison’s strategies that you cited are not specific to movements; they are the way almost any idea spreads: tours and books by its charismatic originator, who also organizes groups of local enthusiasts, trains others to teach it. Bill also developed an academy, an institute, a research farm, a certificate program, and he tried to “copyright” the name. None of that is typical of movements.

So let’s look at the theory that it’s a movement in two ways: Does permaculture share the characteristics of a movement, and does it advance permaculture—is it useful—to think of it as a movement?

You called it a movement without defining what a movement is, so we need to do that to see if the word fits.

Here’s the definition from Wikipedia’s article on movements, quoting authors of major works: “a series of contentious performances, displays and campaigns by which ordinary people make collective claims on others. . . . social movements are a major vehicle for ordinary people’s participation in public politics. [They are] collective challenges to elites, authorities, other groups or cultural codes by people with common purposes and solidarity in sustained interactions with elites, opponents and authorities.”

Nothing in any of that is what permaculturists are doing as permaculture. Permaculture is very explicitly not protest, challenges, claims on others, or campaigns. In the Permaculture Handbook you linked to, Mollison insists on that, and says, “While we realise the value of evidence and protest in changing public opinion, we belong to another discipline—that of real solutions.” He says we are building excellence in “the integrated design sciences,” and “we are essentially designers of practical working models.” No mention of movement or social agenda.

So it doesn’t fit the accepted definition of a social movement. “Movement” gains very little traction on that count.

Then, is it useful to us, in terms of advancing permaculture, to define it as a movement? Movements of the last 100 years or so typically develop political strategies, raise funds to support them, lobby lawmakers to write laws, put initiatives on ballots, organize rallies and protests for the cause. In non-western cultures they use their power via different means to topple regimes and change laws. None of that has been part of permaculture’s development, and I can’t see how doing any of that would advance permaculture. And being a movement has vivid drawbacks: defining ourselves as a social, (or spiritual, or cultural) movement aligns us with particular constituencies and identity groups, just as the civil rights, anti-war, and environmental movements have, which means alienating anyone who does not share that social, political, or spiritual agenda and getting their pushback. As a design approach, it avoids those drawbacks; Republicans and anarchists can practice it equally well, and in doing so, I believe, they will develop the holistic awareness needed to adopt the new whole-systems paradigm. If we force them to join our “movement,” they won’t change, and we and the planet lose.

Also, a movement or a philosophy is developed very differently from a design approach or a thinking tool. We’re not doing most of things that are needed for a movement to succeed, another reason I can’t call it a movement. We don’t attempt to raise consciousness or get splashy news stories via dramatic protest to broadcast our message. We hold classes and teach design. We garden. We create institutes of regional practitioners and hand out certificates. What movement does that? If it’s a movement, it’s pretty much a failure—where are our policy successes?—and we’ve been going about it all wrong. If it’s a design approach, we’re pretty successful, and we’ve been following the strategies of many other developing inter-disciplinary approaches.

Movements have agendas and goals: suffrage, stopping a war, civil rights, clean air, and so on. Permaculturists as a whole have no one goal that we are moving toward, other than a goal so broad, “peoplecare, earthcare” that almost every social movement on Earth could fit into it. A “movement” that can be used to change everything is not a movement; it’s part of a paradigm shift.

It doesn’t fit the definition of a movement, it doesn’t act like other movements, it doesn’t improve the practice to call it a movement, and we aren’t working with it as if it were a movement.

Permaculturists build solutions that can be used by people in movements, and many of us are simultaneously involved in movements (environment, anti-GMO, social and food justice, etc.) which we use permaculture design to support. That, I think, is why we confuse it with a movement, and why some of the agroecology folks confuse their field with the campesino movement: because it can be used by movements to further their goals, just as permaculture can. The Wezel et al. reference you cited said that agroecology has become confusing for both scientists and the public, full of political baggage—Wezel pleaded that people define how they were using the term—and I am hoping to avoid going down that sloppy road in permaculture. Let’s learn a lesson from the agroecology folks before it’s too late, and find a minimal definition of permaculture that accurately describes what it does, and, especially, avoids including what it is not. That’s my project.

So while some people like to call permaculture a movement, I ask that they stop or else stop designing and start doing the things that movement activists do, like organize rallies for permaculture. And I pray that we are not a movement, with all its baggage. I think calling it a movement is at best of no use, and at worst, damaging and confusing for the reasons I’ve given.

As I’ve said, you have written an excellent, cogent, fair, and useful critique, and have gotten me to think about things in new ways. I am grateful, and look forward to more of it. This piece is, I’m sure, the most contentious, and others would more simply develop some of the interesting lines of thought you’ve opened. I’ll chew on this some more, and probably respond again.

Not all movements are protest movements as you have described here. I have done some extensive research on the subject of Permaculture as a social movement for my thesis. Permaculture design can be viewed as the frame by which people who are part of the Permaculture movement use to propagate specific ideals that define the movement. Organizations such as PRI (and others) can be seen as one of the movement’s networks for helping it spread and gain momentum. People who are part of the movement define their shared identities as Permaculturists. I came up with the following based on the writings of prominent social movement theorists.

Social movements are collectives of people united together in joint actions (PERMACULTURE DESIGN) who focus on change oriented goals (MOVEMENT TOWARD SUSTAINABILITY, WHICH CHALLENGE NORMS) or claims with common objectives (PERMACULTURE DESIGN PRINCIPLES) and have some degree of organization and temporal continuity (40 YEARS) ~ (Snow,Soule & Kreisi, 2004).

1. Permaculture developed as a solution to the disequilibria of society (Blumer, 1969).

2. Permaculture people are connected through a loose, non-institutionalized network of informal interactions that includes individuals, groups, formal and informal organizations that are engaged in collective action motivated by a shared identity or concern about environmental and social issues (Rootes, 2004).

3. The collective actions of Permaculture people at the organizational level peacefully challenge socially accepted systems of norms (Melucci, 1980; 1989).

4. Permaculture people call for changes in people’s habits of thought, actions and interpretations (and therefore social change) (Crossley, 2002; Blumer, 1969).

5. Permaculture people recognize and base actions upon shared knowledge, symbols, identities, objectives and

understandings (Melucci, 1989).

6. The ideals of Permaculture people are incompatable with other groups who exercise opposite social values regarding the same resources (Melucci, 1989).

7. Permaculture people take radical steps outside of social norms that push for systemic change and a new order of life (Melucci, 1989; Blumer, 1969).

8. Permaculture people have a smart, articulate and charismatic leader (Bill Mollison) who started the movement (Melucci, 1989).

9. Permaculture people are liked together through a network of organizations and individuals informally linked through collective action and shared identity (Coughlin, 2012).

Excellent, Wendy. I’d love to see your thesis when/if it’s done. I think my principal comment here is, if permaculture has a movement component, the movement is a way of spreading the knowledge system of permaculture design, rather than, as you suggest, the design system being a subset of the movement. The Mollison/Holmgren design system came first (to address social and ecological needs) and the movement, if there is one, arose to propagate it.

I think ideas go through phases of succession while they are being propagated and developed, and the movement portion is a fairly early successionary phase. I think we could describe the Scientific Revolution of the 17th-18th centuries as a movement, but now, at this much later phase, we just have science and its disciplines as settled sets of practices. Movements end as their core ideas become part of societal norms. I think what I’m doing with this “what is permaculture” thinking is figuring out the pattern of permaculture development and succession so we can help it along. The movement phase strikes me as a delicate, easily disturbed and co-opted one.

(Been mulling this over while I work on other projects.) Wendi, the more I think about what you’ve written, the less I agree. First, I’m not referring only to protest movements—the definitions I cited were from major books on social movements by Charles Tilly and by Sidney Tarrow, not on the subset called protest.

Your definition of social movement is so broad that we could plug in nearly any human endeavor and have it meet your criteria. For example: “Social movements are collectives of people united in joint actions (MONSANTO/UNITED NATIONS) who focus on change-oriented goals (CORPORATE TAKEOVER OF SEEDS/WORLD UNITY) or claims with common objectives (CORPORATE MISSION/UN CHARTER) and have some degree of organization and temporal unity (DECADES).

So, of course permaculture will fit a definition that non-specific. It needs refining to exclude things that aren’t social movements.

Then, if I look at your numbered list:

”1. Permaculture developed as a solution to the disequilibria of society (Blumer, 1969).”

No. Mollison, in his autobiography, “Travels in Dreams,” on p.23, says he got the idea for permaculture when researching marsupials in the Tasmanian forest and wrote in a notebook, “I believe we could design systems that function as well as this one does.” Permaculture was his response to ecological degradation and was conceived as a way to design human settlements that mimicked nature. Using Blumer’s logic, all human ideas, from creating railroads to Marxism to inventing the Euro, are solutions to social disequilibria and thus can be movements. Not true.

“2. Permaculture people are connected through a loose, non-institutionalized network . . .”

So are NASCAR fans, gardeners, chess lovers, and so forth. That’s how humans connect. Again, so broad as to include everything.

“3. The collective actions of Permaculture people at the organizational level peacefully challenge socially accepted systems of norms (Melucci, 1980; 1989).”

That means that corporations that peacefully challenge norms (get farmers to use pesticides, shift us from frugality to consumerism and debt, and on and on) are social movements. They aren’t. And civil rights, suffrage, and anti-war were not social movements, since they were not peaceful, which is incorrect.

And so on for the rest of the points: Schools, scientists, and businesses all call for changes in people’s thought; most human groups “recognize and base actions upon shared knowledge;” the ideals of many ethnic groups or competing companies have “incompatible social values regarding shared resources” but they are not movements; charismatic leaders exist in corporations and sports teams, not just movements.

My point here is that, nearly anything a group of people create, do, or advocate can be called a movement while it’s developing: the electric car movement, the kombucha movement, the barefoot running movement; each advocates a shift from a social norm and fits all the criteria listed. So, of course permaculture can be called a movement. But I am trying to get at the most useful and effective way to view it, the core property that reflects the daily actions of permaculturists (which is mostly design and its implementation) and guides and opens up the most opportunities. I don’t think “movement” does that, and “design system” does.

Nearly any idea, behavior, theory, or technology goes through a “movement” stage in its early development. That’s where permaculture is right now, temporarily. A social movement, however, has a finite life. It dies when its goal is achieved, as the anti-war movement did when we left Vietnam, and as the civil rights movement subsided after legislation enacted changes.They are called movements because they move toward a goal. When they reach the goal, they end, and become part of the social norm. However, when/if society is sustainable, we will still be permaculturists, and permaculture will be how we design things. Permaculture is a design system that supports a much larger societal movement toward whole-systems thinking and sustainability, but when we reach sustainability, permaculture won’t go away. Permaculture as a movement is a temporary phase. Design is the unchanging feature. If the movement aspect of permaculture ends, permaculture remains. If the design aspect is eliminated, permaculture is gone. Design is fundamental, movement is peripheral.

Calling permaculture a movement, in any but a very secondary sense, is a basic logical category error. It is mistaking a temporary, successionary feature of all developing ideas—while they are being advanced by a growing number of people and thus are in motion—for a central feature. The central feature of a true social movement is that it is an attempt to shift a major society-wide norm. The central feature of permaculture is that it helps us choose the strategies for designing the physical and social systems that can implement that shift. I can see how easy it is to mistake permaculture for the larger societal readjustment itself, but permaculture is only one of many tools in the huge societal movement toward sustainability. We’ll still be here, designing, when that movement is over.

.

Wow! This is brilliant thinking. Thanks, Toby.

Of the 30-40 permaculture design courses I have been apart of, design is always the subject being taught, not how to organize, coalesce, forward a cause i.e. form a movement. I can’t help but wonder if there is a certain fear factor element in wanting permaculture to be a movement. Such as, if permaculture is not a movement then we have no hope at changing the world under the permaculture banner. Personally, I find far more joy and hope everyday in that there is more food and medicine coming out of the land than I know what to do with, my students are finding meaningful work and rapidly gaining the skills they need to design alternative systems, and there are more and more potential students than I can handle (and so some of my students in the future will have meaningful work educating others). In my own experience, putting our hands and feet on the ground developing functional, regenerative, physical and invisible structures is what advances permaculture the most. Talk is cheap in the eyes of most, and I suspect that permaculture as a movement will lead to more talk and less action.

Thanks and well said! You are providing a compelling description of how you yourself perform, and *teach by modeling,* how the permaculture movement organizes and coalesces.

May I suggest Design Process rather than approach, since at each stage it feeds back on itself, and in some senses never completes. This is true whether of biological or other applications.

Sorry to be incommunicado while this great discussion is happening. I’ve got a small boatload of statistical analysis to get through before tomorrow noon, and then I’ll be back in the fray.

Thanks again Rafter & Toby for great posts – conversations like these shore up (and loose up) the foundations that many of us are working on. The very fact that so many people have differing opinions on it remind me that Permaculture is such a broad and inclusive church. I see it as an umbrella term, and a bit like the British Museum, full of stolen things from around the world, which includes design. Quoting Mollison will only get us into trouble, as things have moved on so much since Permaculture started. I think your original survey shows that. I use the term Permaculture to mean the whole shabang – I’m personally focusing more & more on the cultural/community aspects – and Permaculture Design as a systems thinking approach for sustainable solutions – the ‘How’ that is used to get us there.

So that the comment thread doesn’t become hopelessly long and tangled, I decided to move my response to a fresh post:

http://liberationecology.org/2013/06/25/continuing-the-conversation-permaculture-as-a-movement/

This is interesting Rafter! I appreciate this conversation too, so thanks for creating the forum for it.

I just don’t know how one would teach permaculture as a movement, much less practice it. What does that look like? I can’t get over the fact that permaculture is about design.

What I disagree about is that my position comes from fear. My perspective that permaculture is a design system comes from the fact that it is based in concrete action that yields material results. I don’t fear permaculture entering the messy realm of public policy, legal structures, politics, etc. I just see how permaculture has gotten to create real change in these realms is through on-the-ground design work. For example, let’s look at Arizona. Brad Lancaster and many others in Tucson started cutting curbs to harvest street runoff. The city didn’t like it at first because it was damaging city property. However, through Brad and others educating city personnel about the benefits, they have now created legal structures by which people can pay a very small fee to have the city come cut the curb for them. So it was practical design work of building replicable models that led to policy change. The same could be said about City Repair in Oregon and on and on. That is the history that I’m aware of insofar as permaculture is concerned. If there is any fear in me about this, it is that I might have to create a new term to describe my work if permaculture losses it’s design focus. I don’t want that to happen.

I think you are trying to make the case that permaculture has spread via a movement, but I still contend that it was a group of people spreading Permaculture Design, so we shouldn’t confuse the message with the messenger. It’s like saying Ecology spreads by academia, so academia must be Ecology. But that doesn’t make any sense. I’ve decided to give up on caring about the myriad ways how people spread permaculture, but I do care about how

permaculture gets described through the spreading. That to me is what this definition stuff is all about.

For fun I’m going to end my post with the water harvesters motto, which seems oddly appropriate “slow it, spread it, sink it” 😉 Good stuff, this conversation is!

Yes! Thanks for this, Wendi. The New Social Movement lens is exactly right. Similar observations apply to vegetarian & animal rights movements – they are very unevenly institutionalized, and in many places are carried only by networks of individuals.

[…] Ferguson has also discussed the definition of permaculture on a couple of recent blogposts, debating Toby Hemenway’s article (which I quoted at the start of my own post). Hemenway himself joins in the comments: […]

Bill Mollison gives a clear definition for Permaculture design and a great rule to determine what is and what is not permaculture design. Here’s his definition “Permaculture design is a system of assembling conceptual, material, and strategic components in a pattern which functions to benefit life in all its forms. It seeks to provide a sustainable and secure place for living things on this earth” (Designers Manual, 36)

The prime directive for permaculture design is “Every component of a design should function in many ways. Every essential function should be supported by many component” (Designers Manual, 36)

The permaculture test: Every component must perform a minimum of three functions and beauty doesn’t count. If the components don’t perform three functions it’s not permaculture.

If the prime directive of permaculture is done well all the principles will be realized (except Ben Falks ridiculous 72). This is the underlying pattern that Toby is looking for.

In my opinion most permaculture designs do not meet the definition of permaculture and do not pass the test. I think the current trend is to change the definition to fit a poor design or call it a movement when you haven’t read the Designers Manual and understand what it is. In addition, it seems like every book published since the Designer’s Manual has diluted Mollison’s work and confused the issue. To maintain the integrity of the name we must honestly assess designs to see if they pass the test before stamping them “permaculture”. The test also gives a means to quantify how good a permaculture design is…the more functions a component performs the more advanced the design.

I would like to start a permaculture competition to bring attention to this important topic and advance the practice. Who can create a permaculture design with a component that performs the most functions. My record so far is 19. Can anyone beat it 😉

Thanks for weighing in. That definition is a good one, but doesn’t by any means leave nothing more to be said. I’m not so sure about the “3 functions = permaculture, more functions = better permaculture” idea you are proposing. Ultimately, the test of a design is in the multifunctionality of the whole system, not the components – and by the quality of the functions performed, not just the number of them. The high-quality performance of multiple functions at the level of a larger site will almost certainly involve components optimized for a just a few functions – like a well, or staple crop field, or what have you.

You seem to be a bit of a fundamentalist about Mollison’s writings. For myself, I hope that we don’t have to settle for what got written down in 1987. Our thinking and practice has to continue to evolve if we are going to be more than a historical curiosity.

The PDM is chock full of brilliant and provocative thinking. It’s also meandering, badly organized (that joke of an index!), and leavened generously with mistakes, oversimplification, and plain ol’ bullshit. We need to keep growing, with all the complexity and uncertainty that growth entails.

FYI, I deleted the identical comment you posted elsewhere on the site (liberationecology.org/2012/11/14/wait-youre-studying-what-again-part-2/), and will do so again if post identical comments in multiple locations.

I think the prime directive by the guy who created the system holds a lot of weight. It’s difficult to understand the importance of the prime directive until you’ve accomplished it and seen what it does. Once you’ve accomplished Mollison’s prime directive and lived within the system it creates, what permaculture is will be obvious.

In order to get a component to perform multiple functions it must be connected with many other components performing multiple functions….so to do it well, you have to create a whole system with multi-functioning components. It’s a positive feedback loop that leads to better designs and why he states it as the prime directive.

You’re right in that a well is difficult to integrate and that’s why harvesting rain is emphasized. However, when the well casing protrudes above ground, the color of the casing may reflect or absorb light acting upon it’s surroundings and this can be capitalized on with an appropriate connection. A well can also serve several components with water. A staple crop field is easily integrated into an animal rotation or a succession to orchard or both. This brings up a mollisonian principle “everything gardens or has an effect on its environment” which basically means there is no excuse to not create multi-functioning components and uphold the prime directive.

Mollison’s rule for energy conservation actually states “every element must be placed so that it serves at least two or more functions” and this is tied in with the prime directive. I think shooting a little higher than two is a good goal to move permaculture out of the 1980’s and why I mentioned three.

Still, the Designers Manual offers the best permaculture information. Sometimes it just takes reading it a few times to pull it out. I wouldn’t do anything technical unless I’ve read the latest technical bulletins from the nrcs or other reputable source but the Designers Manual is a great starting place.

Have you checked the components in your designs to see how many ways they function? I’m curious to know what other designers come up with when they analyze their designs.

Once you’ve achieved the prime directive you will know permaculture.

I feel like we are talking past each other at this point, Shawn, so I’m going to let it drop.

[…] http://liberationecology.org/2012/11/14/wait-youre-studying-what-again-part-2/ http://liberationecology.org/2013/06/13/the-convenience-and-poverty-of-simple-definitions/ http://www.permaculture.net/about/definitions.html (orddefinition av […]