Update 6.13.13: If you’re arriving here from Toby’s response to this piece, please check out my reply: The Convenience and Poverty of Simple Definitions.

Deciding that you want to study permaculture is pretty easy. Dangerously easy. Even forgetting our dire need for sustainable design, and considering it just as a straight-up researcher for a minute (taking off my activist-scholar hat), it’s pretty juicey: complex, timely, controversial, and growing fast. And it’s wide open: there is almost, but not quite, zero peer-reviewed research about it. (That’s both an opportunity and a stumbling block, actually, but more on that in another post.)

It’s after that decision – once you’re walking around with this idea in your head that you want to study permaculture – that the trouble starts. This is especially true for higher education, and especially especially if you want to do research. As I mentioned earlier, permaculture suffers from a mild definitional crisis: what is this thing? Our answers tend to veer toward the abstract and all-encompassing. Look at the suite of definitions over here.

For that matter, look at the definition that I came up with back in 2005 (and which I’ve been gratified to see has caught on pretty well). Permaculture is…

meeting human needs while

increasing ecosystem health.

While there are a lot of things I still like about this definition (and I still use it for some purposes)*, it also has its own special muddiness. It implies that permaculture is a criterion. Huh? So then, every time a human need is met, and an ecosystem gets healthier in the process, permaculture is happening? Even if that’s not what the humans are calling it? Even if it’s by accident?!

“Well, permaculture is all-encompassing,” you might say, “It includes everything that’s involved in sustainable human settlement – which is everything! So the definitions reflect that.” OK, fair enough. But it doesn’t get us closer to answerable research questions about the viability and impact of permaculture design.

Which is, I suspect, why the little peer-reviewed research that does exist seems to come from education departments. An all-encompassing definition doesn’t get in the way of a paradigm-shifting educational experience – it probably facilitates it. And the outcomes and quality of that experience can be tracked using conventional social research methods. In other words, questions about permaculture as a curriculum, or pedagogy, might be easier to answer than questions about permaculture-as-everything-sustainable-forever.

So let’s get down to the trouble with how we talk about permaculture. Here it is (or here I think it is): there is a lot of unnecessary confusion involved in the term ‘permaculture’ because it’s being used to refer to different things, from sentence to sentence, without much clue for the listener as to what’s happening. Here is my list of those different things: in any given sentence, you might use ‘permaculture’ to refer to an

-

International social movement (and its regional extensions)

-

Worldview and theory of human-environment relations

-

Design framework

-

Bundle of practices

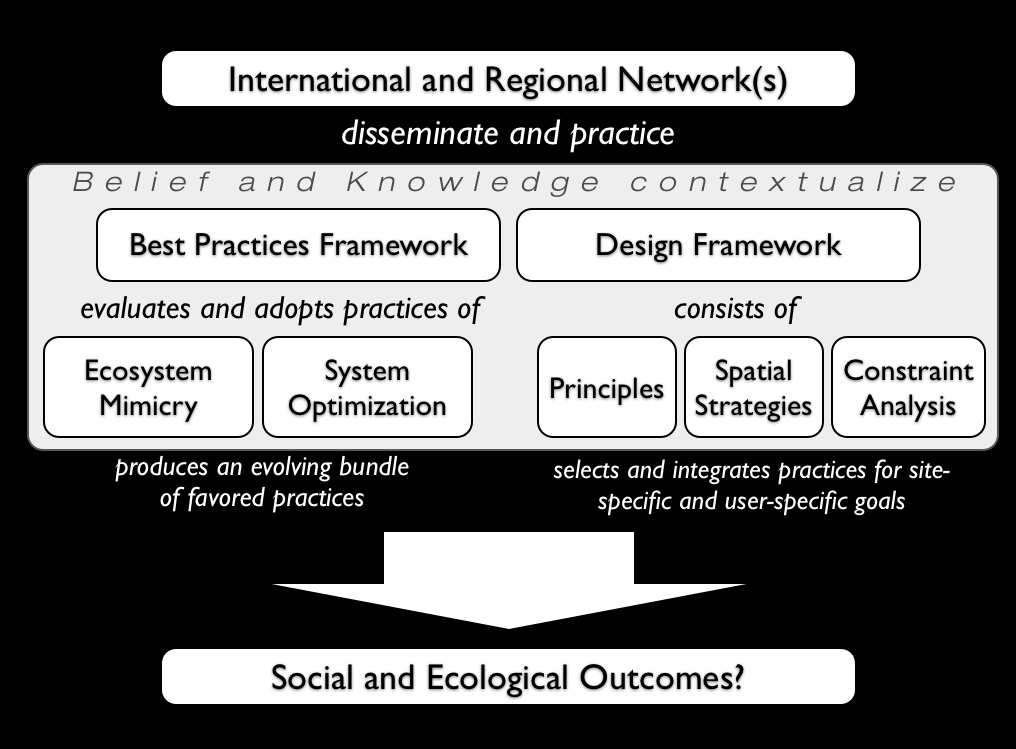

Looking back to the page of definitions I linked to above, you can see that most of the official (!) definitions of permaculture make it out as a mix of worldview (or ‘belief and knowledge’ in my diagram) and design framework. I bet that if you’ve had a decent number of conversations about permaculture, you’ve also heard it used to refer to the movement that carries the worldview, or the practices that are taught along with the design framework.

I don’t need to bet, actually, because as it happens I recently had a chance to ask 698 permaculturists what they thought of each of these possible meanings. I also threw in another one:

5. Profession

…just to see what would happen. I was actually expecting a lot of disagreement on that one.

Here are the percentages of people responding with “Agree” or “Strongly Agree,” to multiple statements starting with “Permaculture is a…”

-

…framework for design and planning: 99.4%

-

…philosophy or worldview: 95.9%

-

…social movement 91.6%

-

…set of farming and gardening practices: 84%

-

…profession 71.4%

Design wins! Wahoo! Followed closely by worldview and movement. I think it’s good to see that practices and profession are the losers, because they are the least distinctive aspects of permaculture. The relative levels of agreement confirmed my hunch, at least tentatively, about what people are using the term to refer to.

My hope, of course, is that this is not just an exercise to bring structure to my research, but that identifying the way we sling this word around will also help permaculturists communicate their goals and proposals with greater clarity. Permaculture is a complex, compound entity, but it doesn’t have to be murky.

What are your experiences with defining permaculture, inside and outside the movement?

Is it as confusing as I’ve made it out to be, or am I overstating my case?

Let me know in the comments.

* That’s the first draft of the definition, that I’m sharing to illustrate a process over time. These days, as you might imagine, I will often specify that definition a bit with reference to design system, movement, etc. – it all depends on the context.

Comments

34 responses to “Wait… you’re studying what again? (Part 2):

What do you mean by permaculture?”

I agree that the muddling is persistent, though I think that through your diagram you have successfully isolated the two streams of permaculture overall that create the turbulence: The WHY and WHAT of placement and practices. Though I would add that we seek less to optimize systems but more so to make them resilient (but can/do we optimize for resilience? such is the rabbit-hole of semantics). If we are seeking a clearly defined niche in the field of ‘sustainable design’ which is rapidly developing around us than I believe it would behoove us to stick more to the definitions surrounding “framework of design and planning” more so than “philosophy or worldview”. Taking organic production as a model, we can recognize that there is a clear set of “farming and gardening practices” associated with organic growing, but that there is also an inherent worldview that may go along with those practices. If we ease on the emphasis of permaculture as a movement, or as I often term it ‘a lens’ through which we solve problems or live our lives, and rather lean more steadfastly upon the design and planning framework then the lifestyle/worldview/movement can follow in the wake of good design and a coherent definition and platform.

Once again similar to organics, maybe the social/personal component is necessary to reach the tipping point after which the process (read: design) becomes paramount to progress and adoption.

We do not need to un-muddle our definitions anymore than we need to seek broader uptake of permaculture design as a framework; but if we believe permaculture to be the powerful and dynamic approach we espouse it to be, than it would be in our best interest (as bastions of the rights of the future) to have clarity in defining ourselves, lest we vanquish permaculture to the dusted tomes of bygone philosophy.

I know it’s a minor point in your comment, Hunter, but I’m fixating on your question about ‘optimizing for resilience.’ This is subtle, but not just semantic. Optimization has usually referred to maximizing a single goal, and minimizing a tightly defined set of inputs. This kind of optimization – for efficiency – produces more and more fragile systems. I suspect that this is a fundamental principle.

When I optimize for resilience, I’m looking at a larger system rather than a narrow goal – and necessarily sacrificing efficiency for redundancy. It’s a very different flavor of optimization. We should expect resilient systems to be less efficient, and be grateful for it.

Rafter—

Thanks for the thought-provoking post, and for helping point out why permaculture is so hard to define. I think we get into a muddle in part because to be well carried out, permaculture requires a whole-systems view in its users, and many mistake that world view, and the shift required to get there, for permaculture itself. More on that below.

I’m glad to see that you, too, think that “questions about permaculture as a curriculum, or pedagogy, might be easier to answer than questions about permaculture-as-everything-sustainable-forever.” I would like to see your own definition (“meeting human needs . . .” etc.) add the word “design” to it or it risks being a permaculture-as-everything statement, too. As you suggest, poking a camas bulb into the ground meets that definition, but it ain’t permaculture design.

I find it helps to think of permaculture as an approach for arriving at strategies and not as a set methods or goals. (I also hear that Mollison has moved away from principles, and talks more about strategies). Strategies are the plan we develop to meet goals, and we carry them out via sets of methods. The statement “meeting human needs while increasing ecosystem health” to me is the goal of permaculture—we want to have that—but not a definition, just as the goal of architecture is to have buildings, but that doesn’t define it. Architecture is a design approach that uses many strategies and tools for planning buildings. In that light, permaculture is a system for developing strategies for meeting human needs while enhancing ecosystem health. Using “strategy” lifts us out of the “permaculture is everything” mess while also not limiting us to a specific set of practices.

We also agree in our dislike of the definition as a set of practices. That risks a cookie-cutter approach. If permaculturists always mulch and build herb spirals, we get mulch where it does harm and abandoned herb spirals. Also, the set of practices available to a permaculture designer approaches all known practices and techniques, from bashing something with a rock to laser levels and querying Google. Almost every technique known to humanity could fit into our toolkit. So a list of “permaculture techniques” approaches the meaninglessness of “permaculture is everything.” Rather, it’s a way to select the most fit practices, and that’s what strategies guide us to do. I’m disappointed that 84% of your respondents agreed it was a set of practices. I strongly disagree, and have been on a bit of a campaign to stamp out what I see as a seriously limiting approach.

Hunter makes a good point in the analogy with organic agriculture, which at heart is a set of practices. There are people who find organic agriculture a serious threat to the social order, and others who see it as requiring a complete set of philosophical views to do well. Veganism is another example. But the working definition is more like a set of practices.

Here’s what may help us in this muddle: Periodically people develop new methods and ideas that require a shift in thinking even to use them, and that can make them very confusing to the observer and even the user. Permaculture is one; organic, though simpler, is another, and there are many others.

A new method or approach can lead to, or require, a radical shift in world-view. Better instruments gave Galileo, Copernicus, and Kepler the means to overthrow the earth-centric world view—and that had a couple of social and philosophical repercussions. Other new instruments and techniques led to the theory of relativity and to quantum mechanics, which influenced philosophy. The first true chemists, like Lavoisier and Priestly, had to think in a whole new way in order to see oxygen as a thing and not as a property (phlogiston), and this ushered in a rational theory of matter and the demise of alchemy and of other magical ways of seeing the world. Permaculture is a similar tool. It is an approach to design, but to do it well you need to think in whole systems, and most of our culture is still grounded in reductionism. Since we have to develop a new world view to use this tool well, we could easily see permaculture as that world view, as a social movement and a philosophy, just as the creation of chemistry, astronomy, and physics came during huge social and philosophical shifts. But after the metaphysical dust has settled, permaculture will probably be seen as, at its core, a design discipline, just as chemistry and astronomy, viewed at this distance from the social milieu that spawned them, are now seen as scientific disciplines and not philosophies.

I think that explains the answers to your survey, where people said, yes, it’s design, but also a movement, a philosophy, and practices. At this early phase permaculture is levering open some of the fissures in our aging world-view of the universe as a machine made of material parts, because to use permaculture well you can’t think in that old way. But it’s not the philosophy itself. It’s a design approach grounded in that philosophy.

There may be something related to learn from this. In their infancy, chemistry, Newtonian physics, quantum theory, and many other disciplines were seen as radical, disruptive, flakey views and were scoffed at. Permaculture suffers from this too. (I just had a national horticultural society withdraw a lecture offer when they learned I was a permaculturist. The field is too fringy and flakey for them.) And the way those other fields got respect was to get data, get systematic, develop a body of coherent, provable knowledge, and demonstrate that theirs was a more useful, effective way of looking at the world. In short, they eliminated the “belief” part of your diagram, emphasized the knowledge part, and became disciplines. The word “discipline” means there is rigor in its practice. I think we could learn from that.

Apologies for a reply that is longer than the post.

No worries on the length, Toby. It’s a good read.

About the high levels of agreement with ‘profession’ and ‘practices…’ The relative levels of agreement tell us much more than the absolute percentage. There is a strong power of suggestion at work with a question like this. People who would never spontaneously describe permaculture as a profession will still agree with a statement that it is one. It’s a pretty reasonable response, that reflects the reality of the milieu – even if not the distinctive character of the approach.

That’s just a first pass – more to come!

Yes, I was thinking, like you, that the way the questions were phrased–is it this, is it that?–predisposed people to agree with multiple ways of describing permaculture. Framing, once again, is key.

I am so glad you have the desire to write this up. I recently scrapped an article I started on this exact topic, mostly focused to persuade people to think and talk about Pc as a design discipline. I scrapped it because it is tough to want to put it out there when so many people are using the term inaccurately. Part of the trouble is that being a whole-system design field it truly takes many, many years for the mind to mature around the concept, which is why I think we need a little more structure for those who practice and teach the subject. At least in the western world, we are so cultured to think in bits and pieces, it probably takes 5-10 years to truly get the concepts in permaculture without trying to boil it down into parts. I highly encourage you to seek out long-time permaculture teacher and practitioner Joel Glanzberg when it comes to this as he is writing some PHENOMENAL material on the topic.

One question I have is around the term “design science”. When you evaluate farms practicing permaculture for your research, are you evaluating it on the basis of design or the practices employed? And, is there any precedent for evaluating a particular design field for its effectiveness or lack thereof solely based on the design principles, methods, etc, themselves?

Hey Jason – thanks for your comment and questions. Can you suggest something in particular by Joel Glanzberg? I’d like to check him out.

I should say – and I think this was unclear in my article – that I’m advocating that just one of these meanings for ‘permaculture’ is correct. I think looking at permaculture itself through a whole-systems lens means that we should probably appreciate its multiple levels and layers.

I’ll be examining both practices employed, and how those practices are distributed through the landscape in spatial patterns. I’ll also be asking questions about why features are located where they are. There are two sets of connections to forge. First, between permaculture thinking and the practical decisions that are made (as shown in the spatial distribution of land uses, among other things). Second, between those practical decisions and the outcomes we can measure at the whole-farm level, in terms of social, ecological, and economic indicators.

Rafter, I’m trying to get ahold of Joel so I can get his permission to pass his work around (I know Toby wants this too). I’ll e-mail you off-list once this comes through.

The research aims seem very multi-faceted, which I think is great. It all kind of goes back to an old question of how does one know permaculture is being practiced? What are the indicators? I tend to think the ethics, principles, and design methods all need to be evident in the systems layout to determine if permaculture design was, and is, being utilized.

I like what Larry Santoyo says about permaculture design. He suggests that the farm, the garden, the building, the alternative currency, etc. are only the by-products of permaculture design, and not permaculture themselves. Permaculture then becomes a verb as opposed to a noun in this sense. It has always felt a little strange to me when people say, ‘this is my permaculture garden’. I tend to think it’s just a garden, and permaculture is more the invisible process that makes it a particularly high-fucntioning garden with a lot of ecological connections.

I like where you are going with your research to determine whether this design thinking process pays off in the form of yield of economics, social systems, and ecological benefits. Are you looking at ecological services at all in this analysis? I know these are tricky to solidly quantify, but I think this is where the rubber really hits the road.

Lastly, a recurring thought around this for me is if permaculture design truly takes a wholistic view it becomes difficult to see a farm as an isolated organism. If we look at the highest generalization of what a farm is, we end up with food production/distribution (in most cases). The wholistic view of food production/distribution isn’t necessarily the farm, but food systems in general. I often think permaculture design might be better applied to food systems first in order to determine what role each particular farm can best play. Of course this varies from place to place, as do food systems, so the complexity goes a bit higher. I wrote an article about this in one of the permaculture activists a few years ago. I think this is a crucial application of permaculture to the area of agriculture, which actually signifies its role as a design discipline as opposed to a farming practice. Liberty Hyde Bailey started doing this back in the day, and was quite unpopular with farmers because of it. Permaculture in general terms is also quite unpopular with the majority of farmers. There seems to have always been a bit of a historical rift between academics (or even perceived academics) and farmers. The beauty of most permaculturists is they firmly believe the map is not the territory and are therefore always interacting with their designs which keeps them out in the fields, forests, waterways, etc. Even with this, permaculture is still quite unpopular with farmers. In my experience working farms, anyone who is not working as hard as you is suspect, and therefore the hammock loving permaculturist will have a hard time being embraced by farming types in general. I know this is quite a generalization, but it certainly is a social pattern. I think the research you are doing to get to the economic yield of utilizing permaculture design has one of the better chances of shifting this pattern, and not just for farmers, but policymakers too.

Dear Toby and Rafter, thanks a lot for your input! I’m a permaculture teacher in the Netherlands. And indeed both biodynamics and organic agriculture are beeing seen as a believe system over here, at least by the powers that be, the head of Wageningen University, he recently wrote a collum about that wich caused quite a quarrel.

Permaculture is so new (our permaculture school started in 2003) that we are working very hard to get it on the map. Having more research to refer to would be very usefull.

And this way of looking at it can possibly even help get us out of the endless methaphysical discussions….

http://permaculture.org.au/2011/12/08/permaculture-and-metaphysics/

I like to see permaculture as a science, urging a paradigm shift and not as a political or metaphysical thing.

People I meet and even students sometimes expect us to preform sjaman rituals or chose one religion over an other wich I think is silly and unrelated to permaculture. It only narrows the group of people permaculture appeals to, or like Julian Assange eloquently said, “All partizanship is lethal.”

For me, the core of permaculture is systems design, as applied to landscapes and human settlements. The existing branches of science to which it is most closely connected are human ecology and agro-ecology (which mirror the duality in the original creation of the word ‘permaculture’ – sustainable agriculture as the basis for a sustainable human culture). However, agroecology is alive and well, and agricultural research is moving up the mainstream agenda, while human ecology isn’t a phrase you hear much of nowadays. Perhaps it needs a revival …

By the way, you may be interested in the work of my university supervisor Tim Lenton (and this is a connection that I am deliberately trying to make with permaculture) – he worked as James Lovelock’s research assistant, co-authoring papers on Gaia theory and Daisyworld, and is now a professor in his own right, looking at the Earth from a systems perspective. He was lead author of ‘Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system’, and co-author on the Planetary Boundaries paper by Rockstrom et al, and a more recent one ‘Anticipating critical transitions’ (Scheffer et al, 2012, Science). This paper examines the behaviour of complex networks eg the financial markets or climate system, in the run-up to a crisis, looking for characteristic behaviour such as rigidity, cascading effects, slowing down etc.

If you don’t have access to journals through a university, having a look at the abstract and emailing the corresponding author usually works a treat.

Regarding metaphysics and so on, there are many belief systems out there, whereas human ecology (how humans obtain food and fuel, and dispose of wastes) applies to everybody.

One final point: annual investment in renewable sources of energy last year hit $270 billion. There are now readily available, cheap, modular, democratic, clean sources of energy that you can implement in your own home. The drop in the price of PV panels (75% reduction in 2 years) is a revolution of global significance on a par with the Arab Spring.

In your diagram (which is generally veru helpful) I think it would be useful to exise the notion of ‘Best Practice’ and, instead replace it with, at least ‘Good Practice’ and/or ‘Good attention and support to that which seems to be emerging and also appears to be in the general direction of the goals’.

Why? Because Best Practice is a concept that, to use a term already introduced here, encourages cookie-cutter approaches (which may be genuinely useful, not to be sneered at in SIMPLE contexts). Whereas I find myself (as a permaculture designer) nearly always working in complicated and complex contexts.

See the Cynefin model (David Snowden) for a more complete discussion of this thinking in this video, for example, http://www.youtube.co/watch?v=N7oz366X0-8 or at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cynefin

This is another way of clearing up our meaning of permaculture design, I think.

Good post and responses. I think to me the missing piece (and I’m unsure how to frame it in your concept) is that to me ecosystem mimicry and principles are fundamentally connected and that the basis of action in permaculture is implementing practices we learn FROM nature. (Thus the ecosystem should inform practices and design rather than the other way around) The practices of sheet mulch and herb sprial distract us from the foundations which are the layering of organic matter to stimulate biological activity (sheet mulch) and the amazing adaptation of plants to microclimate (herb spiral). In this way, we are framing things in terms of being readers of the landcape, then applying the language we as a design process. This inherently requires that we are consistently out in natural systems, observing and interacting with them. I know I fail to make the time to do this again and again and because of it, my permaculture thinking rests more in the head then in the hands or heart. Its getting better over time – but to me this feels like the fundamental invitation of permaculture – that individuals can step outside and cultivate a landscape simply by asking good questions and learning ecology.

Yeah! Thanks, Steve, for making that virtuoso connection between the abstraction of definitions and the concrete of embodied experience. (Typical!)

Your attention to the way in which permaculture invites us to live in our senses, and occupy (!) the landscape, is crucial. Like you – like a lot of us – I would benefit from doing this a lot more. Noticing this connection is great because it points to ways in which worldview, design, and practice are not easily separated. The distinctions I propose in the diagram above break down at a certain point.

Like George Box, the statistician quoted in Panarchy (Gunderson et al. 2002), said, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

There is a theme coming up in these comments about letting the ‘worldview’ aspect of permaculture fall away, so that the brilliance of the design framework can shine through. I think this is a mistake. In thinking about the relationship between permaculture and institutional science and policy, one of the frameworks that has been very useful for me is Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Coming out of anthropology (and ethnoscience in particular) the TEK framework draws attention to the ways in which the complex of traditional knowledge, belief, and practice, constitutes its own kind of science – one that in many cases produces better outcomes than ‘modern’ science.

People who study TEK – a large and diverse field – largely agree on a couple points that are pertinent to our discussion: (1) worldview matters, and (2) ecological knowledge is always politically charged. That’s why the results of trying to integrate TEK and institutional science, over the last decade, have been so mixed. Norms, ethics, and explanations, affect our decisions, and their outcomes, deeply – no matter the landscape management technique we’re applying.

We permaculturists, mixing and adapting ecological knowledge from scientific and traditional contexts, aren’t doing TEK. But we would do well to pay attention to those two principles. In the absence of scientific evidence *directly* supporting permaculture, we’ve gotten to where we are now because of the power of the permaculture worldview, and it’s resonance with the hopes and anxieties of people all over. We downplay it now at our peril.

Then, oh, the politics! I’ve been kicked off the international permaculture list more than once for even inviting people to consider some of these questions. So I empathize with those who propose that we leave the politics behind. 😉 But permaculture, our own hybrid ecological knowledge, is inherently political. Permaculture farmers tell me about how they feel excluded or actively targeted by farm policy that’s purportedly designed to support sustainable agriculture. Official measures of sustainability incorporate NO attention to spatial configuration (and are thereby blind to some of the most important distinguishing features of a permaculture farm). Toby’s invitation to speak gets withdrawn when they find out he’s a permaculturist!

Who defines what sustainability means? And who decides who receives support for doing sustainability? These are fundamentally political questions – not in the sense of traditional partisan faultlines, but in the basic sense of the power to draw boundaries that include and exclude, and to decide who has access to what resources.

This all being said, I’m delighted to keep metaphysics out of permaculture education, and to avoid defining permaculture in a way that aligns it to a particular political ideology. But I know that teaching and doing permaculture invoke a worldview that gives the activity meaning, and makes it worth doing. And I know that however straightforward and fact-based things might seem in the classroom (and they don’t always seem that way!), once we leave the room full of like-minded fellow travelers, the political charge in our work will become apparent again, whether we acknowledge it or not. We have many alternatives of how to frame that worldview, and its politics, but we should not leave it out of our analysis.

Guess I should follow Toby and say “Sorry for the comment that’s longer than the post!”

Instead, I’ll just say that these themes will be expanded on in an upcoming post.

Some examples to bring “permaculture” into some kind of contextual ambit – now working “on-the-ground” – not widely known:

1) “Gaviotas” – in Columbia, S.A.

2) Russian “dachas” – modeled on “Anastasia” Book Series

3) SEE: “One Man, One Cow, One Planet”

I found Patrick Whitefield’s “Spider-Diagrams” in his “The Earth Care Manual: A Permaculture Handbook For Britain & Other Temperate Climates” to be the most productive way to see the interactive relationships in permaculture – without losing clarity or focus – as contrasted with – any kind of hierarchical model of definitions – and – most importantly – FUNCTIONS.

The most precise modeling prize – goes to Howard T. Odum – who does a full energy and “eMergy” accounting of the intersection of human activities and the natural world. This volume is a major modernization of Odum’s classic work on the significance of power and its role in society, bringing his approach and insight to a whole new generation of students and scholars. For this edition Odum refines his original theories and introduces two new measures: “emergy” and “transformity”.

The working permaculture examples that I offered above – have a strong design component – yet as things start to evolve – in practice – a creative and intuitive component – comes into play – that both defies – and – informs – the formal analysis.

Hope that you find this to be of help to your research goals.

– Namaste’ – Bill

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

A style guide – among many possible – for your doctoral dissertation – “THE SOCIOECONOMIC AND CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF FOOD GARDENING IN THE VLADIMIR REGION OF RUSSIA” – by LEONID SHARASHKIN – Namaste’ – Bill

Hey Bill. Sharashkin’s work was very inspiring for me when I came across it back in 2009. It’s too bad that he’s stopped doing research, and moved so strongly in a New Age direction.

Saw Jason’s comments. You can check out my new website: patternmind.org. My book on the subject should be available electronically by March-ish. My premise is that Permaculture is a pattern-based design approach. Everything else are techniques and technologies that arise from that pattern-based lens. How we see, think about and hence act in the world are all “tracks” of how we think, tracks of the patterns of our mind. Hence the book is titled: the Permaculture Mind

Sounds like good stuff, Joel. Thanks for commenting. I look forward to checking out your book!

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] http://www.patternliteracy.com/668-what-permaculture-isnt-and-is http://liberationecology.org/2012/11/14/wait-youre-studying-what-again-part-2/ http://liberationecology.org/2013/06/13/the-convenience-and-poverty-of-simple-definitions/ […]

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]

[…] Permaculture is notoriously hard to define. A recent survey shows that people simultaneously believe it is a design approach, a philosophy, a movement, and a […]